Hitting the news circuit just last week was the sobering revelation that songbird populations in North America have declined by 29% –nearly 3 billion birds – over the past fifty years. The news comes from one of the most robust and comprehensive reviews of the status of the avian community ever completed, led by several prominent ornithologists and published in the journal Science. What is most alarming about the research is evidence that population-level declines were nearly universal among bird species during these few decades, not even evading birds we think of as common – the sparrows, orioles, and blackbirds in our backyards and city parks. The study confirms what anyone who has watched birds for the past couple of decades already can sense – our birds are in trouble and they are sounding the alarm that critical aspects of our natural world are beginning to unravel.

As a bird enthusiast, one of the most immediate reactions I had to this news was a sense of alarm, a jolting fear, followed quickly by encompassing gloom. I can vividly imagine all the many birds now gone, all of the beauty stripped from the world, all of the loss that is likely yet to come. It is almost unfathomable to me a world where the song of the morning Northern Cardinal or the dance of the Purple Martin no longer exists. And yet, here we are – almost a third of all birds in North America wiped from the earth in less than a normal human lifespan. Could the world I experience if I’m lucky enough to make it another 30 years be one without the jolly hummingbirds and majestic herons I’ve known all of my life?

And so I wonder – can our bird brothers and sisters sense this sadness too??? Do they also intuit the loss occurring around them – a loss precipitated by a gauntlet of threats and dangers created by the human species? Can they sense, especially the long-lived types like parrots and raptors, a world with less and less avian presence with each passing decade? Do they worry that every new threat may be the one that tips the scales, signaling an inevitable downward spiral? I don’t know precisely what birds know and understand or what they feel or don’t feel, but it would be foolhardy for me to imagine they are ignorant of it all. After all, birds rely on keen insight, intuition, and environmental intelligence to survive – without such awareness they wouldn’t eat, or migrate, raise young, or escape the jaws of a predator. They are in tune with the fine details of the natural world in ways that humans can barely comprehend. They must have a hunch that something is up.

Long inspired by authors like Jon Young (What the Robin Knows) and Virginia Morell (Animal Wise) I am increasingly convinced that non-human species have intellectual and emotional sophistication and awareness that allows them to understand and make meaning of the world around them. In How Animals Grieve, Barbara J. King makes the case that many species experience something similar to what we understand to be grief – the same feeling I had upon reading the latest news about my avian friends. Evidence is mounting behind this once preposterous claim. By studying brain chemistry and activity in birds, biologists like John Marzluff have demonstrated that birds posses the same hormones, neurotransmitters, and brain areas involved in our own experiences of emotional loss. There is no doubt that birds have the capacity for grief, although there is still much work needed to understand whether that is activated in quite the same way as it is for humans.

Even still, there is no shortage of compelling stories of avian emotion, especially among the remaining few individual birds of now extinct species. Christopher Cokinos, in Hope is the Thing with Feathers, recounts the somber tale of Booming Ben, the last of the Heath Hens (ext. 1932), who, perched atop a tree in Martha’s Vineyard, would call for hours each evening for another member of his species to answer. No bird ever did.

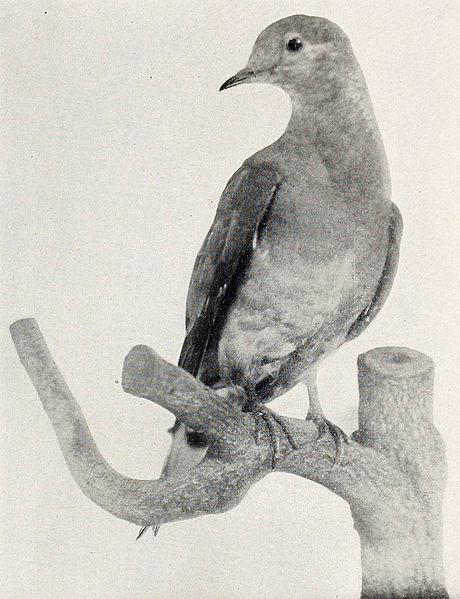

And then there was Martha, the last known remaining Passenger Pigeon (ext. 1914). After her partner (George) expired at the Cincinnati Zoo where they were residents, Martha became despondent. The last of her kind, she was reported to be so morose that she would stare in the distance for days on end before dying herself of what her keepers could only describe as intense sadness. These stories, though perhaps somewhat anthropomorphic, coupled with mounting evidence of animal emotion, are enough to convince me that in some way, the answer to my question is yes, birds do feel loss.

I realize that the sadness I feel at such loss isn’t going to erase the massive threats that face birds today. I am not interested in wallowing in grief for long as I don’t think it is productive to do so. But I am also not interested in sweeping the sadness under the rug, slapping on a smile, and pretending that everything is going to work out if we just focus on positive thinking and creative problem-solving. It isn’t that simple either. Sometimes we need to allow ourselves time to truly feel and become acquainted with the reality of things. Sometimes we have to sit with the expansiveness of gloom – to let it permeate and penetrate our faculties. What emerges is a piercing respect for the enormity of it all.

We may never know conclusively if birds feel sadness in the way that you and I do. I kind of hope they don’t. What we do know, however, is that our own species has the capacity to feel, empathize, and translate complex emotions into tangible actions, if we elect to use said capacity. Through both our rational minds and our affective sensibilities our species is well-aware of the trouble that is brewing for birds and the ecosystems on which they (and us) rely. Our sadness about that fact comes with a significant responsibility to do something about it. Wouldn’t it be a shame to waste the intellectual and emotional capacity of our species by watching such a catastrophe happen right in front of us?

After writing his book filled with the sorrowful stories of now extinct birds, Cokinos himself wrestled with a sense of dejection. He concludes his story by reflecting:

“I thought of the sentences I had written and those yet to be. I thought of how humbled I had become in the face of this daunting and dangerous history of vanished – of vanquished – birds. I have learned much from this history and have realized, finally, that sadness at loss is our best first response. It should not be our only response. We know the world gives us life, beauty and solace. We would be ungrateful if we failed to give that back.” (pp. 336)

Like Cokinos, sadness at the news of shrinking bird populations is my first response too. Yet for the sake of the beauty and wonder of birds, it will not be my last.

For more on what can be done to stop the loss of songbirds, visit here.