I suspect that it goes without saying, for anyone that hasn’t had their head buried in the sand for the past eight months, that 2020 has been a difficult year. Like many of you, I’ve felt a wide range of emotions since March: anger and frustration at the festering racism and bigotry that plagues our fractured country, horror at the all-too-obvious deadly consequences of our inability to protect the very planet we depend on, and sadness and grief at the needless loss of life and livelihood caused both by a deadly virus and the irresponsible behaviors of those more interested in political and religious theatre than in saving lives. Not only has the bad news been relentless this year, but the punches just keep coming (RIP RBG). It’s a bleak time for anyone that believes in human decency, unity, sound judgement, science, or moral principles.

I’ll be frank with you – I’ve recently felt what can only be described as hopelessness, given the barrage of daunting challenges we face. I don’t use that word lightly – it has a grave heaviness to it. But it isn’t an exaggeration. There are some days when I don’t see how we get out of this mess. There are other days when I can’t imagine a bright future at all. I feel lost – wondering what to do next and how to help turn things around.

In environmental science, we’ve added a number of phrases to our lexicon over the last few decades. Climate grief, compassion fatigue, and “solastalgia” are just a few – the last term coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht to combine the words nostalgia, solace and desolation in describing a profound sense of loss, isolation, and powerlessness that accompanies environmental disaster. Solastalgia has been palpable in recent years for those of us who love birds. The relentless attacks on protections for birds in the United States, undermining laws that have existed for over one hundred years, has resulted in profound grief. Even more, there is a weary despair that lingers in the air right now, extending far beyond the egregious disregard for the health of the earth peddled by our leaders. A dark cloud has, thus far, enveloped the year 2020. Although willful ignorance or isolation may conceal it for a while, the cloud looms large.

As I’ve noted on this blog before, my feathered friends play a substantial role in pulling me away from these despairing thoughts – the simple beauty of a cardinal, the boundless energy of a hummingbird, the calmness of a heron. I have lost count of the occasions in which I have entered the woods with a melancholy mood and re-emerged with renewed hope having communed with the birds. Beyond these everyday encounters, however, the story of the entire group of animals known as birds harkens back to another dark time in history. In fact, none of my present-day encounters would even be possible if it weren’t for a few tenacious and persistent avian ancestors that endured a hellish period in the history of planet earth.

A very brief snapshot of avian evolution

The precise evolutionary origin of birds has always been a subject of considerable debate. Birds and their flying reptile ancestors have delicate, lightweight skeletons which do not fossilize well, hindering an exact interpretation of how the birds evolved based on the fossil record alone. In science, information is collected, theories are developed and tested, and informed consensus is reached based on a preponderance of evidence. But new information can always change what we understand. Science, by definition, is never fully settled – part of the great mystery and intrigue of the practice.

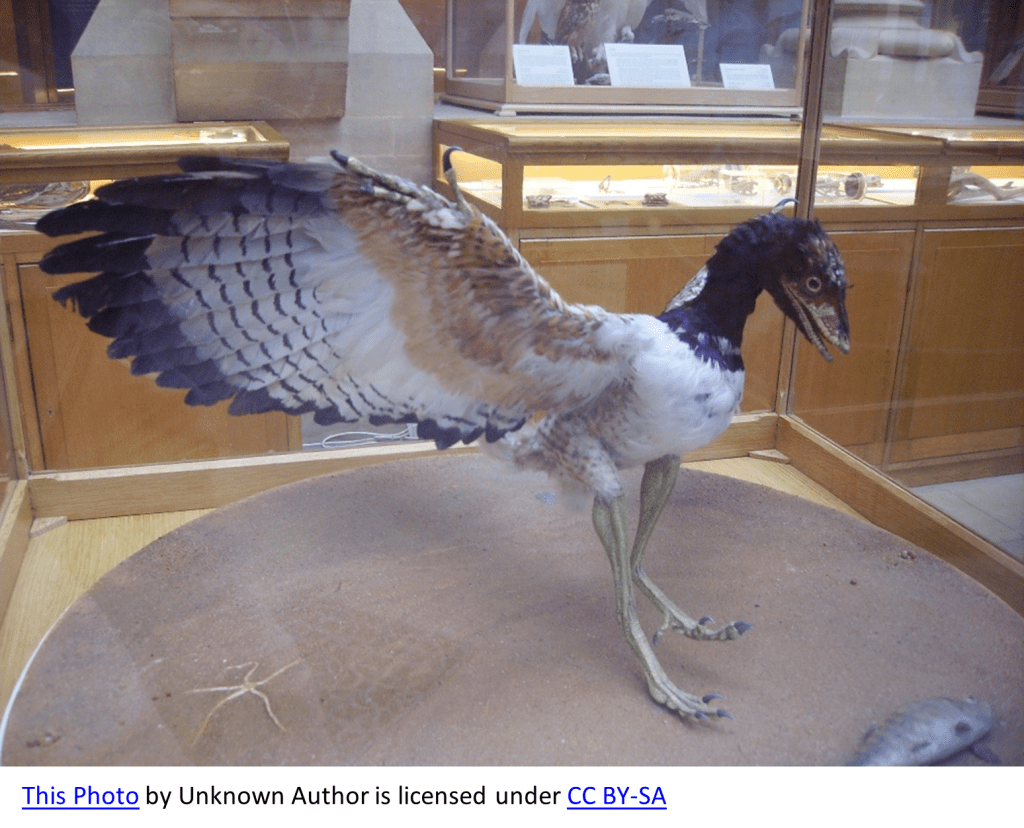

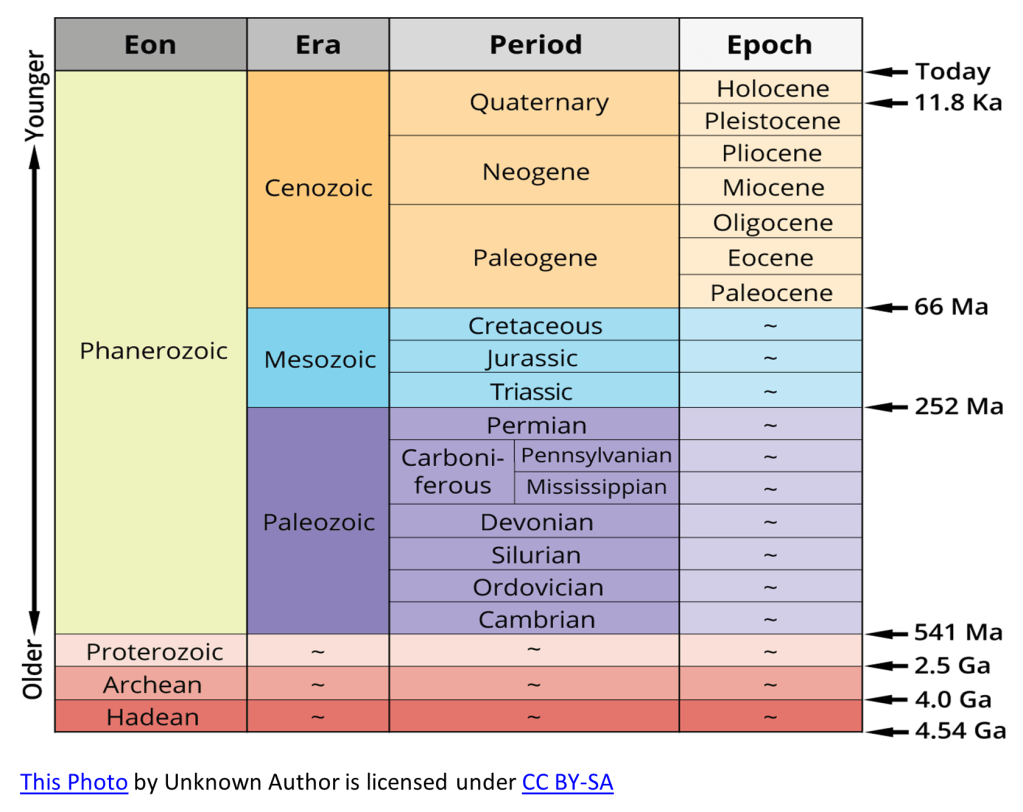

The evidence collected thus far traces the ancestors of birds all the way back to theropod dinosaurs. What is widely agreed to be the first bird, Archaeopteryx, appears in the fossil record during the late Jurassic period. This lightly feathered, winged “bird” and others that evolved similarly would pave the way for many new species during the next geologic period (Cretaceous), a time in which a large group of birds called the Enantiornithes exploded. These birds were once widespread across the planet and quite diverse, leaving behind a complex fossil bird taxon. Members of this group included sparrow-sized birds to birds with wingspans of more than 3 feet!

Along with the dinosaurs, Enantiornithes birds were completely wiped out by the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction caused by an asteroid impact 66 million years ago. One of the pervasive myths about this event was that the mass extinction brought on by the cataclysm happened all-of-a-sudden. While the sheer impact of the asteroid may have erased some species in an instant, for others, extinction came in the grueling months and years that followed. With regard to prehistoric Enantiornithes, studies now show that the impact of the asteroid on global climate caused massive deforestation and the extinction of most flowering plants. With destruction of the habitats on which they relied, the mostly tree-dwelling Enantiornithes weren’t able to adapt to survive.

That could have easily been the end of birds on this planet – snuffed out with the dinosaurs. Can you imagine how horrible this time must have been – to borrow a word I used earlier – how hopeless things must have seemed? A rich, thriving planet with abundant life and diversity was thrown into chaos – riddled with natural disasters, depleted resources, and catastrophic loss of life. Deadly and dangerous forces loomed, driving what once were cooperative alliances between species to morph into dog-eat-dog (or should I say dino-eat-dino) interactions. How could any of the species that remained summon the strength and resolution needed to keep pushing forward in that desolate world?

Despite what was certainly a diabolic period, recent molecular dating suggests that all of the amazing bird diversity that exists today can be traced back to a handful (literally just a few species) of ancestral bird lineages that somehow, someway survived the K-Pg mass extinction event. We call this branch of birds the Neornithes, a group that diverged from the Enantiornithes in the late Cretaceous period prior to the asteroid collision.

For a long time, it was widely believed that modern birds evolved from one transitional shorebird that survived the K-Pg event and that, from there, birds diverged into their modern varieties. There are still some paleontologists who argue for this interpretation of the fossil record. However, with the sophistication of recent DNA analysis, most paleontologists agree that several Neornithes species evolved prior to the extinction, and that a handful survived to give rise to the radiation of modern birds after the event.

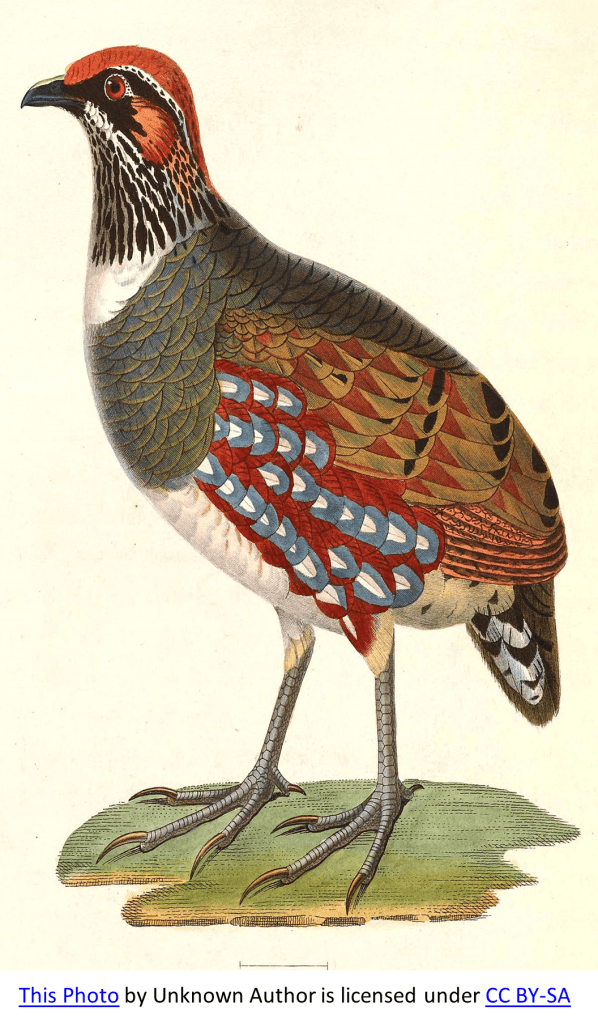

A recent reconstruction of the evolutionary tree of birds suggests that these few surviving species evolved from one small ground-dwelling bird similar to a modern partridge1. In fact, it is the ground-dwelling nature of these few species that evolutionary ecologists believe may have been the key to their survival because they weren’t reliant on the trees that were largely decimated during this time. Whether one or a handful, it was surely no more than a tiny fraction of a tiny fraction (repeated, intentionally) of the birds that existed prior to the K-Pg mass extinction that survived. Those tenacious few species would later give birth to the full beauty and richness of the over 10,000 known species of birds that exist today.

A reason for hope or a hopeless stretch?

I know what you are thinking – this guy must be pretty damn desperate to reach all the way back millions of years to find hope… While I often find that knowledge and understanding of history can and should inform the present, I realize this is REALLY distant history. Go ahead – accuse me of a hopeless metaphorical stretch. I don’t fault your skepticism.

But I have to say that thinking of those few partridge-like bird species, facing an infinitely singed and disastrous world day after day as they set out to find tiny morsels of sustenance just to survive, stirs a hint of optimism in the year 2020 that I’ve not been able to conjure up in other ways. Those small, courageous acts of belief in a better future, whether conscious or not, provided the embers of a fire that today burns so brightly across the vivid, multi-colored feathers of my avian friends. It is the one small kernel of promise that I need right now.

Those of us who love birds, human decency, and basic kindness owe it to the tiny sliver of avian species that kept hope alive 66 million years ago to keep burning embers of hope today. Against all odds, the story of birds reminds us that such kernels have the power to radiate into boundless beauty in the years to come. Now, more than ever, how thankful I am for that beauty.

- Hope, Sylvia (2002). The Mesozoic radiation of Neornithes. In Chiappe, Luis M. & Witmer, Lawrence M. (eds) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs.

Thank. You.

LikeLike

Now, more than ever, I am grateful for your beauty.

LikeLike